Wi-Fi

A guide on how to achieve the highest possible Wireless Fidelity.

There are four key components involved in the distribution of "the wifi" at a consumer household. "Four? I only have one (or two)!" Indeed, most times these components are combined into one or two products, but I find it much easier to split them out into their individual conceptual components. And usually, splitting them out into separate physical components will also provide greater flexibility and performance, too!

ONT

If you're in a rural area, and / or using the cellular network (i.e. 4G, 5G, etc.) to get your internet, this guide probably isn't for you.

In a typical residential home, the internet is accessed via an Internet Service Provider (ISP), who distributes it over fibre to your house, whereupon it is converted by an Opitcal Network Terminator (ONT) to regular cables.

If you haven't already got fibre, do so first before moving on to other areas. It doesn't matter much how fast it is, just that you have it. The quality of internet connectivity that fibre offers is in another league compared to Digital Subscriber Lines (e.g. ADSL) over the phone network, or wirelessly over the cellular data network.

A typical ONT.

Router

The box that most people call "the wifi" is usually an all-in-one router, switch, and access point. It makes sense to split it up into the three constituent components when discussing what it does, and also practically, when optimising a network's performance.

A router does what it says on the tin: route network traffic to wherever it needs to go. It orchestrates the network, and tells devices connected to it how to get to the internet. A good router will be able to process the traffic from many simultaneous devices each making many simultaneous connections.

For example, a cheap router may only be able to properly handle a few (tens) of devices at once, whilst a good router should easily be able to process traffic from many (hundreds) of devices.

If you have an all-in-one router, it has to share it's processing between being a router, a switch, and an access point. Conversely, a dedicated router can focus on doing it's one job much better.

Switch

Before the days of Wi-Fi, everything on a network had to be physically connected via cables. It's still a really good idea to do this as much as possible, because a cable will always be more reliable than Wi-Fi.

"But where do all these cables go? My computer only has one port!" That's what a switch is for: it has many ports. If you have an all-in-one router/switch/access point, it will have (usually four) ports on the back labelled as "LAN". This is the built-in switch. For almost all setups, this is actually fine.

These days, switches are simple and cheap, and not worth worrying over. Make sure it is capable of at least one gigabit (1 Gbps) for each of the ports, and that the total switching capacity is 2×n Gbps (where n is the number of ports).

AP

For maximum detail, read through wiisfi.com

This is where we get to the bit that most people interact with. The actual thing that your devices connect to.

A wireless access point is a special device that acts like a switch, but wirelessly. It doesn't route traffic or do anything else special: it only provides network access to wireless devices. If you have an all-in-one router, the Wi-Fi access point will be built-in. It used to be quite obvious if this was the case, as it would have plainly visible antennae, but these days they are trending towards being hidden away internally.

This is the most important piece of equipment to purchase separately, as you can maximise the Wi-Fi performance, without having to pay for any extra bells and whistles for an all-in-one router/switch/access point. An all-in-one device will never maximise the performance in any one of its areas.

But don't worry if you've currently got an all-in-one system: you can still add a high-performance AP! Just as you can trivially connect another switch to the one built into your router, you can connect an external AP to the switch in your router as well. It's not necessary to replace all of your networking components, as they are all wonderfully compatible and interoperable (i.e. when I say it's three components in one box, literally they physically operate like that, too).

In the following section, I'll go over some general guidelines for optimising network performance, starting upstream and working down to your end devices. Specific advice can only be given by someone who has intimate knowledge of your context.

Guidelines

Specific advice can't be given without detailed context, so here's some general guidelines, working from ISP to your devices:

ISP

A well-known ISP is likely to also have decent access to the wider internet, and a more substantial network with more "points of presence" to get to various bits of the internet. As such, it may be preferable to go with a known quantity than a small startup ISP that may not be as well-connected. This will only have a very minor impact, if any. Optimising this should be last on your list.

Router

In a large household, with many devices connected, a router may struggle to keep track of all of them. Huawei's HG659b is a good example of a router that struggles. If you had fibre internet from 2016-2020ish from Vodafone or Spark, you likely had one of these (probably branded differently). Upgrading your router should be done if your ISP provides an especially low-quality unit, or it is particularly outdated and your ISP hasn't bothered to update it recently. If you purchased a dedicated router in the last 5 years, it should be fine for many years to come.

Switch

Make sure you never run out of ports for all your wired devices, and try to maximise how many wired devices (vs. wireless) you have. Where possible, don't daisy-chain switches from room to rom, but get a high-speed centralised switch to distribute as far and wide as possible, adding small (4/5/8-port) switches in other rooms, as required.

Access Point

This is the tricky bit. Whatever you currently have is almost certainly poor, and if your ISP provided it, it is guaranteed to be less than ideal. Newer Wi-Fi versions can perform better than older versions, though the factors affecting Wi-Fi performance are nuanced and many.

In general, you should prioritise (in order):

- Frequency band, at least 5 GHz (higher is better)

- Antennae / spatial streams, at least 2, preferably 4+ (more is better)

- Wi-Fi version, at least 5, preferably 6E (newer is better)

- Multiple Access Points

Multiple Access Points?

Yep, you can have more than one! Marketing gurus will call this "mesh networking", which is hogwash. All this actually means is having more than one Wi-Fi Access Point that is connected to the same network, and uses the same name when broadcasting Wi-Fi, so your devices can seamlessly transition between them.

The most important piece of advice here is: every Wireless Access Point needs to have a dedicated Ethernet cable connection back to the router!

If you already have multiple modern APs and your Wi-Fi still sucks, don't but any more gear! Pay as much as it takes for an electrician to run an Ethernet cable to connect them to your router. All else is secondary.

Don't buy Wi-Fi extenders, they cannot help you. Put in a cable and a regular AP instead.

Wi-Fi Access Point placement

The physical location of the Access Points around your house is also important. If you have a two-storey house, place one towards one side on one floor, and the other to the other side on the other floor (with Ethernet cables between them). This way, each covers two-ish floors and one half of the house.

Don't be tempted to hide them away in a cupboard or TV cabinet. Wi-Fi likes free space, and doesn't want to compete with furniture, and especially not with other electronic devices! A large TV is nearly impermeable to Wi-Fi, so try to arrange it so that the TV is not between the Access Point and most of your house.

Where possible, place them high up and away from things. On top of a tall cabinet or bookshelf is quite good. If you can walk around your living space and see it from most places, it's a good place to be. "Ugh, it's so ugly though!" Fortunately, modern devices are getting to be a bit more aesthetically-minded, with some nice white options that don't look like a dead spider anymore. It's not a great idea to buy purely based on appearance, but if you're tossing up between two or three options, it's perfectly fine to go with the one that feels better.

Wi-Fi Access Point configuration

Now on to the bit that you were probably expecting: "follow this one simple trick to double your wifi speed!"

Now, I'm not saying that you will be able to double your Wi-Fi speed... but the difference between a poorly-configured network and a well-configured network with the same hardware can easily be double.

Frequency band

Wi-Fi is a shared resource. Only one thing gets to use any particular chunk of the frequency spectrum at one time. If one device is downloading a video game, another device can't be uploading photos at the same time. Of course, they can take turns really really fast (tens or hundreds of times per second), but it still can't be simultaneous.

That example might not sound too bad, but it gets worse when you extrapolate to the 10, 20, 30, 50, etc. devices that you have all connected at once. It gets worse: you're also sharing with your neighbours! Yeah, their network might be called a different name, but it still has to share the same frequency spectrum. As such, it's really important that you share it well.

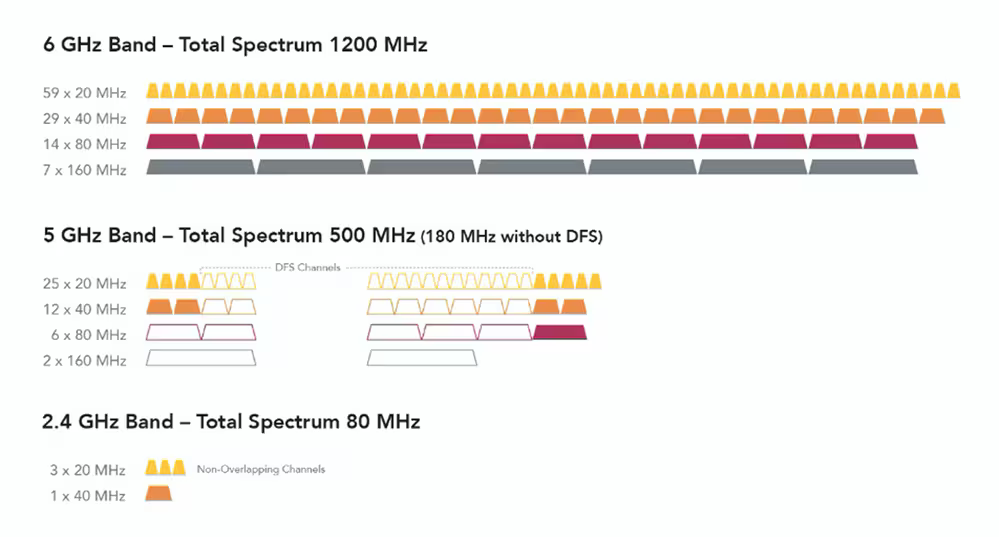

Image from Cisco.

For 2.4 GHz, read the 20 MHz line, for 5 GHz, read the 80 MHz line, for 6 GHz, read the 160 MHz line.

The total available Wi-Fi specturm is split up into "channels" that can be used, so that everyone isn't literally sharing the exact same frequency. If you are communicating on different, non-overlapping channels, then you and your neighbours Wi-Fi won't be competing at all, which would be ideal.

To orchestrate this, you can use any number of "Wi-Fi Scanner" apps on one of your devices to see who's doing what nearby.

As is hopefully evident in the diagram, the 2.4 GHz band is ... quite small. In that tiny little bit of spectrum, you have to fit all classic Wi-Fi devices, all IoT (a.k.a. "smart home") devices, all Bluetooth devices, everyone's wireless keyboards and mice, and your microwave. Phew! I don't think they're going to all fit neatly, and they don't really. At this point, I consider the 2.4 Ghz band a lost cause.

Competent Wi-Fi devices will support the 5 GHz band, which has been a thing since Wi-Fi 5 in 2013. It's an utter disgrace that you can still buy brand new "modern" devices which don't support it (i.e. most "smart home" things). Whilst it is much wider (and thus faster) than the 2.4 GHz band, it's still not ideal, as a large portion out of the middle is unavailable due to broadcast TV already living there. Most of the rest is also very underutilised (or for cheap Access Points, inaccessible) due to requiring the Wi-Fi broadcasting device to monitor its surroundings and make sure it doesn't interfere with broadcast TV. These channels are called "DFS". All that said, there are a few bits of spectrum left at either end of the 5 GHz band, which is enough for fast Wi-Fi, as long as you don't have too many neighbours also using it.

Actually modern Wi-Fi devices will support the 6 GHz band. Please don't buy new end devices (phones, laptops, computers) that don't support it. Unfortunately, manufacturers have been exceedingly lazy at adopting it, known as Wi-Fi 6E (from late 2021), to the point where Apple only started selling devices with it in late 2024. Given the absolute chonkiness of spectrum available, it's disgraceful how slow the uptake has been. Alas, due to legal reasons (a.k.a. the governments want to sell it to cellular network providers), only about half of it is available currently, depending on which country you are in.

End devices

An important note: Wi-Fi works on the least common denominator. Eh, maths? No, when two Wi-Fi things talk, they fall back to the oldest (read: slowest) version they both understand. The newest spangliest Access Point will be forced to regress to decades-old Wi-Fi technology if your phone is a decade old. Or even if your phone is brand-new, as manufacturers have become really lazy about keeping up-to-date with modern Wi-Fi technology. Did you know we're up to Wi-Fi 7 already?

Likewise, the fanciest shmanciest phone will be utterly kneecapped if your Wi-Fi Access Point is still talking Wi-Fi 4 (from 2009).